Folks who've been reading the blog know one of the reasons I model the 1930's:

to understand the world my grandparents lived in. My great-grandfather, after all, had a ten acre apricot orchard in the hills above Hayward. I never heard many stories about the ranch and about the fruit industry from family, but the stories I've heard about Santa Clara Valley farms gives me some hints about what his life was like.

But, you know, if you do enough family history, you'll be amazed what stories you'll turn up.

I took some vacation time last week, and decided to spend a day looking through Alameda County deeds to learn more about the farm. I managed to find the original deed, which was a nice find, and a few other details about the property, but nothing that really told a human story. On the way back to the Valley of Heart's Delight, I stopped off at the Hayward Public Library, just in case they had something interesting. There wasn't much - a couple old city directories, and a shelf of local history books. One was a spiral-bound history of local agriculture with some decent stories, but again, nothing special. But leafing through, I saw a familiar last name, and found a couple pages on my great-uncle and his beekeeping. In between the bee stories, there were some quick details of his father's farm. Wow - where'd they get those? From an oral history interview they did with him back in 1983!

Back home, I sent off a note to the Hayward Area Historical Society asking if they had a transcript of that interview. They're in the middle of moving their collection, so I really was expecting either no answer, or a curt "sorry, can't get to that stuff, ask again in six months." Instead, I got an answer the next day from one of the archivists. "We don't have a transcript of the interview, but we do have the original reel-to-reel tape. It's not in the best shape, but it's listenable. Oh, and we're sending you a digital copy of the audio."

And that was it - I had the audio of my long-gone great uncle telling about the ranch, his father, and the apricot business. After all I've been learning about drying yards, dried fruit buyers, and small family farms, my family's story now seems much more real.

Joe and Mary Machado Azevedo, and two of their kids.

Joe Azevedo's Fruit Ranch: My great-grandfather, Joe Azevedo (Jose Machado de Azevedo), the son of a whaler, was born in 1857 on the island of Sao Jorge in the Azores. Joe's father, Antonio, had done pretty well in the whaling business, and had returned to the islands with enough money to build a new house on the hillside above the village. That earned Antonio the nickname "Casanova" (new house). The nickname stuck around for a century; my Uncle Carl was able to ask a cab driver in the '60's to take him to Tony Machado Casanova's house, and the cab driver went there as if he'd done it a hundred times.

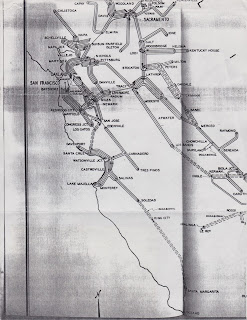

Joe emigrated to California in the 1870's. He roamed around the State, working in a livery stable in San Francisco and also as a shepherd and sheep-shearer for the Miller and Lux company for several years. In 1884, he took his savings, plunked down a thousand dollars and change, and bought a ten acre farm at the top of the hill above Hayward. The property wasn't much; it was a dry and hilly farm, with the top end of a canyon dividing the property, but the right scale for a family farm. This was probably the best Joe could do; most of the good land had been claimed long before, so newer immigrants were often chased into the marginal land on the hills. The Piccheti family on Montebello Ridge near Cupertino's another example, as would be any of the families up in the hills behind Wrights Station.

Joe's new land had been part of Guillermo Castro's Rancho San Lorenzo. Guillermo's gambling habit cost him the land, sold on the courthouse steps in 1864 to Faxon Atherton, a San Francisco banker and land speculator. Faxon and partners had bought the land in hopes of encouraging small farms to feed San Francisco, and slowly sold off smaller lots. The land on the top of the hill didn't sell til Atherton's widow sold it to Frank Enos Garnier in 1879, who subdivided it further until Joe bought the acreage in 1884.

Joe planted an orchard and vineyard on his new land. He used the vineyard for home-made wine. Carl remembered his father pulling up the vineyard, perhaps as Prohibition came through in the late 'teens, with more apricot trees going in their place. Those apricots were the primary crop, with enough cherry trees to justify the occasional harvesting, and assorted other trees for family use. Carl remembers helping his father harvest cherries once for the canneries. Occasionally, Joe planted peas in between the rows of trees.

None of the trees were irrigated: as Carl puts it:

Interviewer: How did they irrigate those trees to start out?

Carl: Never did irrigate. Never put a bucket of water on any tree.

Interviewer: Is that right?

Carl: If it was today, I think I'd have put sprinklers on there.

Interviewer: Um hm.

Carl: Yeah, it would make a good, it would make a… but they had good apricots. Sure. We made good mountain fruit, you know?

Interviewer: Well, they're much sweeter when you don't irrigate them.

Carl: Yeah.

Interviewer: Then...

Carl: Yeah, they were really good. Everyone knew. The buyer would know. The buyer would always come out to get dried apricots. They were looking for that!

The farm. Notice the drying flats laid out to the right of the house.

Those mountain-grown, unirrigated apricots might not have produced as heavily as the trees in the flat lands, but they made up for it in taste. Carl remembered that the dried fruit buyers would climb up the hill to the farm every year to convince Joe to sell his crop to them. "I'll give you six cents a pound today." "I don't know, I want to wait a couple more days." The buyer would troop back down the hill. Coming back closer to harvest, they'd offer an additional half-cent, and Joe would promise his apricots to the buyer's company. Carl just remembers the buyers were from the different big companies and didn't remember a particular company, making me suspect that Joe was selling to Guggenhime, Rosenberg, or California Packing Corporation rather than to the Sunsweet co-op. Unlike Vince Nola's stories about farmers selling to the same company every year, I suspect Joe was bouncing between packers depending on the price they could offer.

When the apricots were ripe, Joe hired crews to harvest and dry the fruit. He ran a dryer on the property for the crop, with drying trays and dry yard carts to carry the full trays out to the closely-mowed drying yard, and a sulfur house for preserving the fruit. His wife, Mary, would have her hands full during the harvest cooking for the workers. Carl remembers spending every Fourth of July cutting apricots, and the other kids got drafted to help pick up deadfall fruit.

Joe also dried fruit for the neighbors with smaller orchards. He didn't charge for the drying as long as they cut the fruit. Once dry, the fruit was weighed in the scale just inside the fruit shed, bagged into burlap sacks, and hauled by horse and wagon down to the depot for shipping to the packer.

But making a living off ten acres of mountain fruit took a bunch of extra work. During the winter, Carl remembered his father assembling a crew for pruning the orchards of other land-owners. Even with that, money was tight. The family says that they never wanted for food - they raised hogs, quail, and chickens for meat, kept a cow for milk, and had all the fruits and vegetables they could eat, Cash was a different story, and always scarce when the doctor needed to be paid, or supplies needed to be bought. "I don't know how they lived… but it was pretty rough".

Joe, in 1938, with a full tray of apricots

Joe Azevedo died in 1939, 82 years old. The kids ran the orchard for a couple more years, but eventually gave up on working it commercially because of a lack of interest. Carl, always fond of the ranch and the business, would have liked to keep it going, but just wasn't up for doing it alone. It couldn't have been a money-maker, especially at that small scale.

And so the orchard sat idle for years, with family and friends hauling out buckets of fruit for their own use, but no major harvesting or drying. My mom remembers her two cousins, future golf pros, practicing their swings in the orchard with the fallen fruit.

And it eventually came to an end. Joe's kids, hit by taxes, assessments for a sewer extension, a lack of interest in the orchard, and the pressures of their own families, finally sold the land in the 1960's for development. It took the buyer a good ten years to build, but eventually the ten acres of Joe Azevedo's "fruit ranch" got planted in in a bumper crop of tract homes.

I doubt any of this story is unique; a hundred families in the Santa Clara Valley could tell the same. If you go hiking up behind the Pichetti Winery in Cupertino, you'll hike through the remains of some old pear orchards, another set of dry-farmed orchards that couldn't compete with the productive farms on the valley floor. If you wander through Sunnyvale, or San Jose, or Campbell, you'll see the tract houses that replaced the Johnson's orchard, or the Kirk orchard.

And when the trains on my layout stop at Alma, or at Campbell, or at Wrights, you might see a model of a horse and wagon unloading sacks of dried apricots from another small mountain orchard - maybe from a Portuguese farmer, or an Italian orchardist, or a Croatian rancher. That's also Joe Azevedo's fruit heading east on those boxcars.

See Part Two for more on the ranch, and how my great-grandfather sold his dried fruit.

[All photos from our family's collection. Great, heartfelt thanks to the Hayward Area Historical Society, not only for sharing the tape, but sending me a copy during the one week where I'd have the time to listen, transcribe, and research its contents.]