So let's recap, shall we?

- Robert wants to build a model railroad with scenes that match places he likes in California, and wants realistic and busy levels of traffic so he can run lots of trains switching boxcars around the layout.

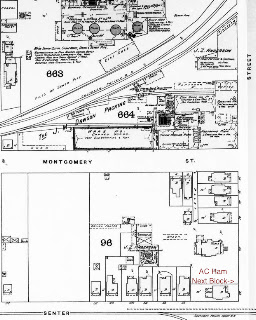

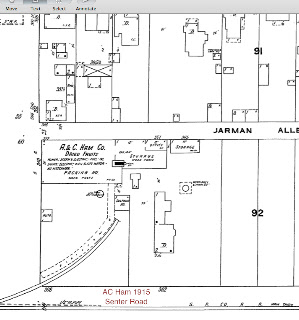

- Robert chooses the San Jose - Los Gatos branch because it has lots of busy canneries and dried fruit packing houses, so there will be lots of boxcars to move back and forth.

- Robert researches the individual canneries, like the Hyde Cannery in Campbell, to understand what to build, and because he's hoping he'll learn interesting historical tidbits that make for good stories about the models and the layout.

- Robert finds the Hyde Cannery was closed after 1928 or so - the era he models. Robert is annoyed.

- Robert, being curious, goes to the County Recorder's office to understand why the cannery was closed in what ought to have been a prosperous year.

- Robert finds documents describing strange mortgages and leases starting several years before the closure, making him wonder about financial difficulties.

- Robert becomes very fearful that his next step is to take some college coursework in forensic accounting… all to figure out how to build an HO model of a cannery.

Which leads straight to the question of the day. When I'd

researched the Hyde Cannery's financial state a few weeks ago at the County Recorder's office, I'd turned up one interesting lease that I didn't understand:

At the same time, Hyde leased all the cannery's warehouse space to the Lawrence Warehouse Company for $1.00 on a month-by-month basis. (7/16/23, book 37 pg 368, as well as renewals in 1924) I don't know if this was a way to raise funds, or if there were legal reasons to have an official warehouse company handling those buildings, but overall feeling I get is that Hyde needed capital.

We also know that Higgins-Hyde did a similar leasing of their warehouse space to Lawrence Warehouse. So… leasing your warehouse, lock, stock, and barrel to another company: sign of desperation, or sign of having very clever accountants?

An interesting story in "The Sunsweet Story" by Robert Couchman actually explains why Hyde's lease of their warehouse might have actually been very smart. When the California Prune and Apricot Growers (Sunsweet) got started in 1917 as a grower co-operative, Sunsweet contracted with sixty-five dried fruit packing houses to receive the dried fruit from the Sunsweet-associated growers, and pack the incoming crop.

When Sunsweet got the 1917 crop packed, they found out working with someone else's packing companies wasn't good. First, they noticed that different packers had wildly different costs, often out of line with what packing the fruit should have cost. Worse, one packer (George N. Herbert Packing Company) refused to turn over $100,000 they'd collected for the crop. Sunsweet responded by putting liens against

"22 carloads of packed fruit, 200 tons of fruit in the firm's warehouse, and a large orchard owned by Herbert. By its prompt and energetic action, the association got its money back and avoided further trouble of this kind."

And Sunsweet learned their lesson: working with the individual packers sucked, sometimes in small ways, and sometimes in very big, not good, very bad ways. And they learned that slapping liens on property that someone cares about often gets their attention quickly.

But what to do instead? Now, they could have just opened their own Sunsweet-owned packing houses. But California law at the time put a nasty little restriction on companies: they couldn't borrow money against product in their own warehouses… but they could borrow money against unsold product if it was stored in someone else's public warehouse. (I suspect this was a way to make sure you weren't slipping the product out without paying off the lender.)

So Sunsweet issued another $750,000 in stock, and started buying packing houses. But they called their lawyer and accountant first, and made sure (and here's the trick) all the packing houses were bought in the name of the Growers' Packing and Warehousing Association (GP&WA), which was a company fully owned by Sunsweet. Sunsweet could now take dried fruit from the orchardists, box it in preparation for sale, and put it in the GP&WA warehouse. GP&WA would give them a receipt for whatever they'd stored in the warehouse, and Sunsweet would take the receipt to the bank and, if necessary, borrow money against the fruit now in the safe and protected hands of Growers' Packing.

This little accounting trick explains why Sunsweet Plant #8 in Mountain View had Growers' Packing and Warehousing Association painted across the building, but everyone really knew it was Sunsweet Plant #8 - it was there just so the folks in the warehouse remembered their paychecks were signed by Growers Packing, and not by Sunsweet.

Oh, and guess which packing house they bought first? Yep, George N. Herbert's plant on Lincoln Ave. in San Jose. I wouldn't have trusted him with the 1918 crop either.

And for George Hyde, it's now easy to understand that if he ever wanted to borrow money against the unsold canned fruit or dried fruit in his warehouse, he needed to get it out of his hands. For whatever reason, he decided against making his own company, and so instead called up the very-large Lawrence Warehouse Corporation up in San Francisco, and invited them over to run his warehouse. Hyde would roll his prunes and fruit cocktail into the warehouse, hand it to the Lawrence Warehouse folks, and give them some money for storage fees. He'd get back a warehouse receipt from the very upstanding and very detail-oriented Lawrence Warehouse staff. If he ever needed to borrow some money for the short term, he'd then take those warehouse receipts down to the bank, and walk out with some hard cash borrowed on reasonable terms that he could use to buy more prunes, more apricots, more cans, or more crates.

And if you want to build a model of the Sunsweet plant, or the Hyde Cannery, you don't really need to know about the rules about borrowing money against finished goods in warehouses, or whether the staff in the Hyde Cannery are wearing "Hyde Cannery" t-shirts or "Lawrence Warehouse" t-shirts. At all. It's completely irrelevant, and if you care, it means you've crossed over from a nice model railroad hobby into some strange history/accounting obsession that can't be healthy.

Which means I'm either really strange, or I've started on a path to a lucrative career in corporate forensic accounting. But if I ever had to build models of buildings in downtown San Jose, I know that the building holding George Hyde's accountants ought to be pretty swanky, for it sounds like they knew how to earn their fee.

[Additional information: The official term for opening a public warehouse at a business is called "field warehousing", and it can be done to borrow against both raw materials and finished product. The September 1922 Western Canner and Packer gives a bit of history on the company, and notes that Lawrence Warehouse was one of the early companies doing this business.

The President of the Lawrence Warehouse Company also wrote an article for the February 1923 Western Canner and Packer about the advantages of field warehousing. He raises the point that the system is helpful when railroad cars are scarce (as happened during the rail strikes during the summer of 1922), for it means that the canner isn't forced to immediately sell and ship the whole crop after canning to pay expenses. Instead, the canner can keep product in their warehouse and ship it as bought, borrowing against the warehouse's contents to pay the growers and other suppliers.

This justification also highlights the big change in the dried and canned fruit industry after 1918. Before the US entered World War I, canners and packers would often sell the crop ASAP to speculators who would hold the product and sell it over the year when prices were favorable. The canners didn't have to worry about warehousing space or shipping during the off-season, and also didn't care about price fluctuations.

Anti-profiteering rules during World War I discouraged the speculative wholesalers from holding product during the war. After the war ended, the wholesalers realized they liked not taking on the speculative risk, and instead bought from the canners and packers only as they needed product. The canners then started holding more stuff in warehouses during the off-season, had to staff the warehouse for shipments, and also had to pay more attention to prices. Now that the canners weren't immediately selling the crop, having ways to borrow against the slowly-selling pack became more important. Field warehousing appears to be one way the canners made sure they had access to cash as they slowly sold each year's crop.

There are specific rules about how a field warehouse is run; the Yale Law Journal in September 1960 cites that the items to be "warehoused" are segregated from the rest of the borrower's stock in an area leased for a nominal sum to the warehouse company, and demarcated with signs and physical barriers to warn folks that the contents have a lien against them. The warehouse company takes possession of the items when they enter the warehouse and issues a receipt that can be given to the bank in a loan, and is only supposed to release the products when the receipt is returned. Warehouse companies got a fee - usually a percentage of the value of the products stored - for being responsible for the stored items, and were on the hook for the value if the items weren't there when a creditor came calling. One of the larger court cases in field warehousing came when a public warehouse company controlling storage for a food oils company turned out never to have received the oil that they'd issued receipts for.

Although field warehouses were run as separate companies, they were often run by employees associated with the original business because of knowledge of how the business worked. Some considered this risky for the warehouse company because the employees might have a conflict of interest, but that's how just how things were run.]

President Roosvelt today had one of the pleasantest and one of the most unpleasant experiences of his entire journey. The pleasant experience was at the Felton Big Trees; the unpleasant one here at San Jose.

Now I can only guess what the President said about that fearful penance, but I know what other members of the party said, and one of them put it tersely in this fashion: