See the previous article for a history of the Bean Spray Track-Pull Tractor.

Normally, I’m not much of a fan of making models “because they’re cool”; I’d prefer to focus on models that I can use on my model railroad, rather than build some cute models that will just get in the way. I'll usually describe projects that aren't appropriate for the layout as "spec(ulative) projects" in a pejorative sense. I don't have much storage space for random models, and would prefer to focus on stuff that will improve the layout.

However, the Track-Pull caught my attention because of a great publicity photo, the San Jose connection, and because - to be blunt - I was bored.

The publicity photo, from History San Jose’s collection, shows a whole herd of Track-Pulls rolling in front of Bean Spray Pump on their way to the Southern Pacific freight house on San Pedro Street. It’s a great shot, both for the Track-Pulls and the Mission-style Anderson Barngrover headquarters in the back of the photo. When I saw the image a few years back, I knew I wanted to do something with that scene, and saved it away in a set of photos I keep around for inspiration.

Last month, I was looking for a little 3d printing project, and remembered those wacky Bean Spray tractors. “Huh, I wonder if I could 3d print one of these.”

Unlike some of the other models I’ve done, there’s precious little information available on the Track-Pulls, and only a few examples still in existence. (If I was smart, I’d also drive by a few lots around San Jose that have rusty farm machinery, just in case there's an actual Track-Pull tractor hiding nearby.) The nearest actual Track-Pull is at a museum up in the Sacramento Valley - reachable, but I'm not enough of a tractor fan to drive up there just to get measurements of a model.

I did a bit of searching on the Internet, turning up a few historical documents and a bunch of photos from the tractor restoration crowd. The best I found was an article from the October 30, 1919 issue of Motor Age, where the magazine reviews the tractor. Motor Age describes the Track-Pull’s engine portion as 30 inches wide, 43 inches high, and six feet long. The tricycle rear wheels were 66 inches apart (though a separate magazine review claimed it was only five feet wide), and the whole machine had a length of 110 inches. Beyond these rough numbers, there’s no other data on the Track-Pull apart from photos.

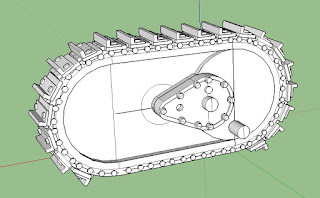

With the little information I had, I started trying to draw the Track-Pull. Like most of my models, I sketched my version of the Track-Pull in SketchUp. I used the rough dimensions, but eyeballed nearly everything else from the few photos.

To get started, I first modeled the Track-Pull in terms of rough shapes, and slowly refined and detailed the model. The caterpillar tread assembly was the first bit; I guessed at an overall size, drew its overall shape, then slowly added the treads and machinery. To increase my confidence, I printed out that assembly on its own just to prove that it could print, and so I could actually see the model in the flesh. (That's a nice aspect of having a 3d printer in my office - I can print out half-done models just for the encouragement, rather than having to send to Shapeways only when I've got a model that I'm willing to spend the money to print.)

Once I had the tread, I started roughing out additional parts of the model - first the gross details such as the outriggers, then the rough shape of the engine and radiator. I then started throwing detail on each piece, sort of how movie model makers throw on "greebles" - random detail - to make their models look more realistic.

This model was a good deal more complex than many of the models I've done for the model railroad. One trick was to work in terms of subassemblies. I used SketchUp's "group" command to make the larger assemblies (the tread, radiator, fuel tank, and outriggers) into single elements. When I needed to get to a hard-to-reach section of the model, I'd select the group that blocked access, and would move it so it was ten feet above or below the model. I could then move the part back into place easily.

I also added 3d parts for much of the piping, such as from the radiator to the engine and back. Normally, SketchUp has lots of problems with curved and round surfaces; having pipes intersect or turn right angles is particularly painful. Because many of these pipes were small (at most 2-3 inches across), I instead drew all the piping with hexagon shapes, and hand-edited the intersections between piping.

For this model, I also printed the model in HO and in O scale both to see the detail and just for the fun of making a larger model. The HO model can print as one piece (with some extra supports to cut away); the O scale model had to be printed with the engine and tread as one piece, and the two wheeled outriggers as a separate part.

These models aren't complete and are still missing features. One obvious omission are the dual wheels for controlling steering and engine speed. As is, these are still impressive models.

Now, the Track-Pull isn't my usual sort of model to build, but it was a fun project. Better yet, it's a nice reminder how the 3d printer really broadens my modeling. Even a few years ago, my only choices for an orchard tractor would have been a die cast or plastic model (maybe one of those modern John Deeres I bought a while back), or else a detailed but pricey white metal kit such as any of the really nice Holt bulldozer tractor kits available from Rio Grande Models. 3d printing gives us the chance to get a wider selection of models.

Drawing those models also gave me the chance to find some interesting stories about how one particularly crazy tractor design came from San Jose. Crazy startups aren't just a 21st century creation of Silicon Valley.

Great thanks to the Flickr user who took pictures of the Track-Pull at the Hendricks Agricultural Museum up in Woodland.