A while ago, we heard Edith Daley’s descriptions of the folks coming down to Campbell to work in the canneries. Thanks to David Pereira, we can put some faces next to those caricatures. David, you see, has quite the connection to Campbell canneries, with his great-grandfather, great-grandmother, grandmother, and grandfather all working for the least-known of the Campbell canneries.

That cannery, as all the serious Campbell historians know, is the California Canneries, located just north of the Ainsley cannery. California Canneries is often forgotten; it didn’t have a high-profile local owner like Ainsley or Hyde; it didn’t have the brand recognition of Sunsweet's dried apricot business. Its buildings didn’t survive. It didn’t host the Doobie Brothers like the Farmer's Union Packing house. California Canneries does have a Hindenburg connection, but that all happened Back East, a long way from Campbell.

[ NO PHOTO OF CANNERY AVAILABLE -

NO ONE KNOWS WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE...

YET]

California Canneries was a San Francisco-based canner, started before the turn of the century, but run during the 20th century by Isidor Jacobs. The cannery’s home office was in San Francisco, in a wooden cannery building at 18th and Minnesota. The original building survived up until last year, with the California Canneries sign still visible from the 18th St. overpass across the SP tracks. It finally lost out to UCSF’s new campus, and was torn down for student housing. There’s a couple mentions of a Napa outpost, but nothing definite. However, in the expansionist era just after World War I, Jacobs came down to Campbell to kick the tires on a cannery.

California Canneries, 18th and Minnesota, San Francisco. Torn down. (Google Street View)

The cannery that Jacobs was eyeing was the Orchard City Cannery, run by Perley Payne, son of James Payne (who Payne Ave. in San Jose is named for.) Perley had started a cannery just north of the Ainsley plant in 1910. Payne’s Orchard City Cannery suffered during World War I; while Ainsley was selling to London, Orchard City primarily sold to Germany, and all its customers were on the wrong side of trenches, barbed wire, and mustard gas... a bad way for a cannery to make a profit. So they didn't make a profit, and Payne ended up selling out to Jacobs in 1917; he ran the cannery for the new owner for a year, but washed his hands of the canning business and fell back to orchard labor. His son noted he had quite a gift for grafting walnut trees.

“Campbell, the Orchard City”, lightly notes that Perley Payne’s son played in the rafters of the cannery building “and [was] reprimanded for his escapades.” Perley Payne Jr., in his own words, told a much more realistic and bittersweet story. He highlighted the dark side of trying to hit it big in the canning business when he talked about how his father handled the business failure. Perley later attempted to organize the workers in the local canneries.

“You see, after he lost his cannery, he kind of felt he was disgraced. And I felt, and my wife too, we really felt bad about it, because, he kind of lived on his knees the rest of his life. He depended on his brothers and his sisters when he wasn’t - like one time I remember, we didn’t work for about two or three months it rained so much here that he had to ask them for money all the time to keep us going, you know. I remember he used to charge groceries at Field’s Store in Campbell and I was working and I would take my check to Field’s Store and cash it and pay so much to Fields on dad’s bill and take some down to the gas station and Fred, I forget his last name, anyway, the guy who owned the gas station - He had a charge there, and I’d pay him, too. And I had, outside of the sorry part here, my aunt and uncle, my uncle George and my aunt Aileen — after my uncle George had died, my aunt Aileen told me, "You know George and I were figuring on sending you to college, but we figured you were too irresponsible. And here I was taking all my money that I earned for five years — all of it went home, except for what I did spend to buy that Model T Ford. All of it went home to help my mother and dad with the grocery bills and whatever else they needed. The only thing I kept out was for a haircut and a little bit to go to a show once in a while, something like that. (Perley Payne, Jr.)

Jacobs, meanwhile, managed to do reasonably well with the property, running the cannery through the 1920s and early 1930’s. But the Great Depression was lethal for canners, and California Canneries declared bankruptcy in 1932. The Campbell property went to Fred Drew, who had just bought the Ainsley Cannery. The flagship San Francisco plant went to Jacob’s broker, Moritz Feibusch, who rebranded the company as Calbear Canneries. Feibusch died in the fire on the Hindenburg airship in 1937, putting an end to California Canneries.

The Place

There’s not much evidence of California Canneries. I’ve seen its name on Sanborn maps and on an SP track diagram, but I’ve never seen a photo of the cannery. There’s a corrugated iron warehouse just south of Fry’s on Salmar Ave that must have been built for the cannery, but a tin building with a linoleum dealer and an irrigation contractor is nowhere near as photogenic as Hyde Cannery’s brick buildings closer to downtown. (The Campbell Museum does have a photo of the warehouse along Salmar Ave., but we don't see the cannery in that photo.)

California Canneries, Campbell Ca. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1920

In the 1920 Sanborn map, Harrison St.is to the left and the railroad tracks cut across the page from southwest to northeast. Ainsley Cannery is on the bottom. Perley Payne grew up in the house on the corner of Harrison and Hopkins. Hopkins no longer exists; both canneries are now under a row of townhouses.

The 1920 map shows four structures: the cannery (one story, 15’ high, corrugated iron with a wood floor), a separate boiler house, a box nailing shed, and a 10,000 gallon water tank. Southern Pacific railroad valuation maps suggest the railroad spur was installed in 1919 as part of the Jacobs improvements, and extended further to the north in 1926. The railroad map also describes the cannery building as 83 x 138 feet, but doesn’t list the size of the warehouse.

Havens-Semaira Cannery, Campbell Ca. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1928-1935

On the 1928-1935 Sanborn map, we see Havens-Semaira Cannery running the cannery; they were founded in 1935 by John Havens of Oakland and S. J. Samaira of San Francisco. Havens had run the Sebatina Canning Company in Sonoma; S. J. Semaira had been importing dried fruits and nuts.

The Sunburn map shows that the cannery expanded to take more of the lot, and the turf dealer warehouse appears to the north. The boiler house has moved, and there’s several more accessory buildings including the kindergarten, and garages. The building is still wood, and the loading platforms are now on the north side.

And A Photos Turns Up

That’s awfully dry. We know the size of the building, the materials, the size of the fuel oil tank, and the size of the kindergarten. But we don’t know anything else about the cannery and the people.

Luckily, David turned up with an employee photo from 1926. Many large companies had group panoramic photos taken during the 1920’s, and the cannery photos are particularly interesting because they give us an idea about both the number of folks working at a cannery, and the ethnic groups that made it up.

David has the photo because it contained four of his family - his great grandfather and great grandmother, his grandmother, and her future husband. His great grandfather was a carpenter; his great-grandmother and her two daughters worked at the canning tables. David was also told his grandfather is somewhere in the photo; he likely met his future wife working one summer.

1926 Employee Photo, California Canneries, Campbell. Courtesy David Pereira

View the photo in high resolution here (7 MB). Spot anything interesting? Mention it in the comments!

There’s a lot in this photo - more than 200 workers (48 men, 7 women who look like office workers, and 158 women from the canning tables.) There’s a shot of the tin building that held the cannery. There’s a box car, and houses.

The People

Let’s start with the people. We’ve got five sources to tell us something about the people in this photo: the 1920 census, a 1920 San Jose City Directory, David’s family story from 1919, Edith Daley’s article from the same summer, and Perley Payne’s stories of growing up in Campbell.

The People: The Census

Census data gives us a starting point about who was living in Campbell. The 1920 census had around 1300 people in Campbell township. Most were American; if we count the families where at least the head of the household was foreign born, we find about 25% of Campbell came from immigrant households. There were 59 Italians, 52 Portuguese, 44 English, 28 Swedes, 25 Canadians, 15 Danes, 12 Germans, 12 Austrians, 10 French, 9 Japanese, 7 Norwegians, 6 Spaniards, 5 Scots, 4 Swiss, two Finns, two Russians, and one Australian, one Irish, and one Pole.

These numbers seem a bit lower than I would have expected. By 1920, immigrants were huge part of cannery workforces in other places (as evidenced by Del Monte's employee newsletter having sections in multiple languages, and the size of the Italian and Portuguese communities in San Jose and Santa Clara.) However, the group photo shows more workers that look American than I expected. I could imagine Campbell wasn't as interesting a place for new immigrants. The land was probably expensive because it was good soil and well irrigated (compared to the east side); projects like the Kirk ditch brought water from Los Gatos Creek to orchards as far away as Willow Glen. The land had also been settled early. Lesser quality land - drier land, or hillside land - might have been all that the new immigrants could afford to work. Campbell also might have been a little less welcoming of new immigrants; a 1930 editorial cartoon in the Campbell Interurban Express sounded like they still weren't terribly pleased by the newcomers, ten years after the Johnson-Reed act in 1924 limited the number of immigrants from Southern Europe, and banned Asian immigration completely.

The ethnic makeup does match Perley Payne's memories:

Interviewer: “I know there were lots of Mexicans in Campbell.”

“We had no Mexicans in high school at all - or grammar school. We had Italians, Portuguese, Yugoslav, two Japanese, and that was about it. The rest of us were just uh, people…. A bunch of [cannery workers] came out of Dos Palos every year [to work at Ainsley].

(Listen to the Perley Payne Jr. interview or

read the transcript.)

About a hundred of the Campbell residents listed occupations related to canning. (See this spreadsheet for a list of all the cannery workers in the 1920 census.) Most were “laborer, canning factory", with the occasional owner, superintendent, or foreman or forewoman. Those numbers are a bit skewed; the census was taken in January, so it omits temporary help. The people willing to list occupations were likely also the workers with sufficient seniority or skill to stay around Campbell during the off-season. (Still, although there's a lot of older men declaring themselves to be cannery workers, there's also still some twenty-somethings declaring that canning is in their blood.) We also only see occupations for the men. Very few women listed cannery work as their occupation.

Generally, only the professional women show up in the occupations. Of the hundreds of women who must have worked at the cutting tables, only Mary King of Sunnyside Ave. listed her occupation as “pitter”. Four women declared themselves as forewomen: Alice V. Hutchins, 55 years old; Clara B. Baldwin, 42; Lulu V. Holmes, 34; and Minnie Lewis, 65; they were responsible for managing the cutting floor - choosing where people sat, handling discipline, ensuring quality. All the other women who spoke of their canning connection were clerical. Emma Swope, 52, was a bookkeeper at Ainsley (and listed as corporate secretary in the 1920 city directory.) Elizabeth B. Hall, 18, was a bookkeeper. Charlotte Thiltgen from Meridian Road, 17, listed her occupation as “saleswoman”. Mary Miller, 36, listed herself as manager of one of the cannery cafeterias. None were recent immigrants, or even children of recent immigrants.

We’ve got Perley Payne, builder of the Payne Cannery still listing himself as owner of a canning factory, while Solomon Jacobs, operating the cannery, listed his job as “manager, canning factory.” Warren Shelly, superintendent, will eventually be the Vice President of the Ainsley cannery in 1933.

On the men’s side, most of the cannery workers are British or American. Archibald Braydon, 32, born in England, lists himself as foreman at a canning factory. So does Leigh Sauders, 49, living at 26 Rincon Ave, and Thomas Mendel, 53. Braydon and Mendel explicitly list themselves as Ainsley employees in the city directory, and Saunders certainly seems a likely Ainsley employee. (If this was modern day, I could imagine salesmen from the London office spending a year working at the cannery so they can better extol the virtues of Santa Clara valley fruit in England and Scotland.) George Sloat, 57; Claude Gard, 42; Clarence Whitney, 54 all show up as foremen. There’s a couple night watchmen; Dudley Chaffee, 61, is boarding with Solomon Jacobs, so we can guess he’s working at California Canneries; Edward P. Green, 60, from Wisconsin, is also serving as night watchman for one of the other canneries. Harry Bloom, 49, and Arthur Cramer, 48, list their occupation as stationary engineers, running the steam boilers. There’s also some hints about which occupations might be more prestigious. Frank Peterbaugh, 19, lists himself as weigher, which I assume required literacy and a certain amount of responsibility. John F. Cooper, a Scotsman living at 27 Campbell Ave., declares himself a shipping clerk. William E. Spreegle, 29, of 21 Everett Street (where’s that?) is a box maker.

The majority of laborers are Americans. Out of 58 laborers, there’s 14 that are either foreign or children of recent immigrants: 5 Portuguese, three Italian, two Irish, two Canadian, and one Russian.

The other big surprise is that most of the fruit-related processing jobs were canning. There were exactly two workers in all of Campbell who said they worked in packing houses: Frank Pererbaugh (19, weigher), and Fred Griggle (34, laborer).

The People: David's Family

So let's compare that with David's family stories.

Anton

We think of the Santa Clara Valley as primarily settlers from the rest of the U.S., with new arrivals in the 1880-1920 time range coming from Italy or Portugal. The census data suggests that Campbell was still predominantly native-born. Anton, David’s great-grandfather, wasn’t; he was born in the Ukraine. He’d been a machinist in Portland, Oregon, but he became a carpenter in the Santa Clara valley, perhaps working in box-making, or perhaps on maintenance of the cannery. His wife, Lena, was from Hungary. The family lived on Harmon Ave in San Jose (Meridian Ave. near Auzerais), just on this side of the Del Monte cannery. Lena and her daughters were working the cannery line; all three were seated in the front row for the photo. From the census data, they were a bit of outliers; there weren't a lot of chances to talk in German (which David said was their primary language.)

Lena and her daughters

David’s grandfather, a Portuguese kid, was somewhere in the crowd according to the family story; he might have been one of the overexposed faces on the right side of the photo - a mix of young and old men who might have been ferrying the fruit into the canning machines. Some of those men would have been the laborers showing up in the census (though I imagine many of the folks we see in the photo are summer workers who didn't show up in the census records at all.) Perley Payne Jr. would have had jobs like this, too.

The Laborers

We also get a bit of story from Perley Payne, Jr. He worked in the canneries when he was a teenager, always waiting until he was 18 when he could work more than 8 hours and make 40c an hour like the men. Although Perley's father had been a business owner, Perley went straight to the socialists, organizing for the cannery unions and eventually leaving for the Spanish Civil War to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. His oral history not only documents his time as a labor organizer, but hints at who lived in Campbell and who worked in Campbell’s cannery.

(Listen to the Perley Payne Jr. interview or

read the transcript.)

Mostly it was Italians and Portuguese women that worked in the cannery. My grandmother worked there. My mother worked in the cannery. My sisters all worked in the cannery…

[Most of the Cannery workers] lived in Campbell, and they knew Mr. Ainsley. They knew the man who owns it. They knew who he was and he had a restaurant for them for lunch. He had a camp where people would come and stay from Dos Palos and other parts of the Valley, they could come and stay during the summer. Of course, us young guys were always down there looking for girlfriends, you know.

Perley's story definitely matches the census records. The two Japanese families, the Makadas and Jios, lived over on Leigh Ave. Wakichi Jio and Suyezo Makada were farmworkers. Portuguese and Italian families both were farmworkers and farm owners; the women of the families represent a lot of the faces in David's photo, even if they didn't explicitly refer to their work in the canneries. Perley's mother also didn't include cannery work as her occupation, but she also had four kids under the age of 7 in 1920.

The older, no-nonsense women in the front row might have been Perley's family, and perhaps floor ladies, managing the women at the cannery. Minnie Lewis or Alice Hutchins might be one of the older women in the front row.

The Floor Ladies

The Women Perley Tried to Date

The young women workers might have been the ones he was chasing after work, or might have been some of the folks from the Central Valley who came to work in the cooler Campbell climate.

Edith Daley, meanwhile, talked about the iconic and stereotypical. There was the city girl who was in Campbell for spending money. The girl with the gingham and the bow, perhaps, and the oh-so modern haircut? Or was she working in the office?

"The City Girl"

"The '80's Material Girls"

The two girls who wouldn’t have looked out of place in a 1980’s new wave club looks like they’re having a good summer.

There was the San Francisco family, here as much for the change of pace as the pay. Their tent might have been the one with the Victrola.

"The City Family"

There was the little Italian girl, the hardest worker of the lot, who would make sure she’d hit 5 or 6 dollars a day. She was a new immigrant, and she was getting money to live on.

"Edith Daley's Hardest Working Italian Girl"

There were also the bookkeepers and clerks running the office, much like Jennie Besana would have been doing this season down at the Contadina cannery in San Jose. The woman with the upturned hair and the long necklace is a giveaway - that's the last thing she would have had around the fruit side of the cannery because of all the exposed machinery. Any of these women could have been the bookkeeper or saleswomen we saw in the census data.

"The Bookkeeper"

"Management"

I’m torn whether this stern looking woman is a floor lady, or a woman from the business or sales side of California Canneries. The pearls are a much safer choice for cannery jewelry, and the haircut’s quite a modern length. Or perhaps this is Mary Miller, the no-nonsense queen of a cannery cafeteria?

For a final photo, here's a close up of the men on the left hand side of the photo. The leftmost kid has what appears to be a holster; at first I thought he had shears, but didn't see any other men with similar equipment. Then I remember my dad's summer job - he worked at Hunt's in Hayward one summer, and was responsible for punching a worker's ticket when she completed packing a tray of cans. I suspect this is the kid responsible for doing the punching at California Canneries that summer.

The Punch Kid

The Plant

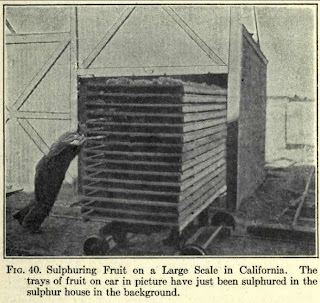

Meanwhile, the machinery didn’t stop humming. Newspaper articles mentioned that Jacobs overhauled the plant in 1919, the peak year for many canneries. He started construction on May 13, but they were shipping apricots by July 9. The photo of the building shows the corrugated iron and simple posts for the cannery; it’s definitely designed for quick construction. For us model railroaders, the corrugated-iron buildings are very familiar; one of the long-time kit manufacturers, Campbell Scale Models, had a bunch of building kits that duplicated these sorts of structures. Campbell got most of their inspiration from the Los Angeles, area, but the California Canneries photo highlights that quick-and-dirty corrugated iron buildings were popular up here in Northern California, too.

The photo takes place on the angled loading dock along Hopkins Ave., a dead-end street paralleling Campbell Ave. that started at Harrison Ave., passed between California Canneries and the Ainsley Cannery, and quickly crossed the SP tracks to end at the cannery housing for the Ainsley cannery. Perley Payne grew up in the house at Hopkins and Harrison, hidden in the trees in the photo. Perley’s father must have hated the traffic from the cars coming to his former cannery. There's a bunch of cars all parked along Hopkins there; the cannery must have generated quite a bit of traffic and parking problems for Campbell.

The Sanborn map shows three houses along Hopkins that might have been annoyed by the traffic. The westernmost house was 80 Harrison, at the corner of Harrison and Hopkins. The Paynes still lived there in 1920, even though the records hint they no longer owned the cannery. 25 Hopkins Ave was next; George Sprague and his extended family were living there; George declared himself a cannery laborer. I'd guess he was a California Canneries employee, and he's probably one of the fifty-something men in the photo. His son-in-law, George Archibald, had the easier job; he was a salesman at a (presumably not-self-service) grocery store. The house closest to the cannery, 35 Hopkins Ave., apparently went with the cannery, for Solomon Jacobs, the manager, lived there in 1920. Dudley Chaffee, the night watchman, boarded with him.

Left side of photo towards Harrison Ave.

The location for California Canneries must have been sweet; I've heard from children of packing house owners that dealing with the line of trucks waiting to drop off fruit in season can be quite a chore; having their own dead-end street must have given California Canneries a bit more wiggle room when the trucks backed up.

By the time Havens-Semaira was running the cannery in 1935, the loading dock where this photo was taken was long gone; the cannery had built out to the edge of the street right-of-way, and the loading dock was now around back in the middle of the lot. For the houses that bordered the property along Harrison, they must have had a lot more problems with trucks idling and noisy unloading.

So now we know what California Canneries looked like. We know why Perley Payne was bitter about losing his cannery. We've got an idea about the

ethnic make-up of Campbell in 1920. (I wonder how much things change in 1930?) And finally, we've also got some faces and names to put next to all those workers who canned the Santa Clara Valley's apricots in the summer of 1926. David's family stories, Edith Daley's observations, Perley Payne's memories, and the census data all give us some hints about those folks in David's photo.

Great thanks to David Pereira for sharing the photo and allowing me to include it here. The Perley Payne interview was recorded in 1999 by San Francisco State University's Labor Archives and Research Center. Census data came from ancestry.com, though I could have avoided a ton of typing if all the data was available in a processed way.

Spot anything interesting in the photo? Talk about it in the comments!