Luckily, we learn more over time. Jack ended up learning more about the YV than anyone else I can think of, and wrote a book about it. And me - well, I started out choosing the industries along the track based on which names sounded better, but every year I’ve learned a bit more about San Jose, the Los Gatos branch, and the canning industry.

And every year or so, I discover some picture that shows me a side of the railroad I’d never seen before. This photo, for example. I found this in a set of railroad photos on Flickr that were put online by the Barriger collection at the University of Missouri, shows the tracks in San Jose at the Western Pacific crossing. It’s a place that appears on my model railroad, so this photo gives me lots of details about what the area looked like, what the buildings looked like, and also what little details I ought to add to my model.

It's also a photo I thought I'd never find - an uninterrupted shot of some underused tracks cutting through the canneries and dried fruit packing houses on the edge of San Jose, showing more weeds than track. It's not a pretty shot, and it's not an action shot, but it shows a scene of San Jose that every distractible schoolboy saw on the way home from school - a photo few people would have ever taken. And it wasn't taken by a schoolboy, but a railroad executive.

Link to BIG VERSION of picture at Flickr.

The Industries:

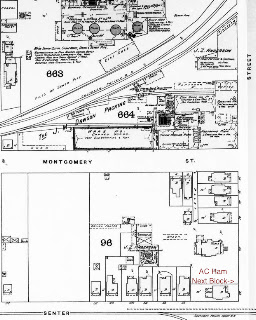

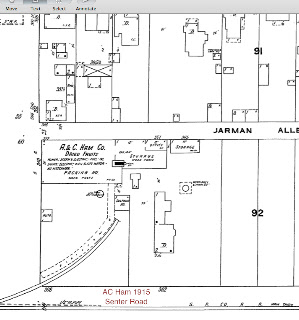

It may not look like much, but this photo is filled with major industries. The corrugated iron fence and barbed wire top protects the Standard Oil depot. In the distance to the left, you see the roof of the large, wooden Sunsweet Plant #6 packing house on Lincoln Avenue - originally the George N. Herbert Packing Company. That little one story building in front of it? It’s listed on a 1950’s Sanborn map as “sack storage”, probably for Sunsweet. That packing house is the same era and the same rough construction as the J.S. Roberts packing house I’ve been building recently. The chimneys behind Sunsweet hint at the Contadina cannery, packing tomato paste.On the right in the foreground is the sawtoothed former Virden Packing cannery; by this time, it may already be used for wine storage. It’s also got that loading dock on the side, also probably an SP siding. The masonry building on the other side of Lincoln Ave. would have been a cold storage building (I’d guess for pears for the canneries), and then in the far distance is the United States Products cannery, packing in glass for extra shelf appeal.

The Details:

For detailing a scene, this is a beautiful photo. For example, the WP crossing was controlled by a switch tower through at least the 1930’s. That tower would have been just to the right of the scene You can see signs of its existence here - derails on both the left and right sidings / drill tracks to keep cars from rolling over the crossing and blocking the tracks. You can also see wood framing the ditch under the tracks which held the rods that controlled the derail.If you look a bit further out, you’ll see cross bucks and a banjo crossing signal in the distance where Lincoln Ave. crosses the tracks. If I had any questions about appropriate signals for the busy Lincoln Ave. crossing, I now know. You’ll also see the searchlight signal a bit further out, indicating that the SP finally did put signals along the Los Gatos branch. There’s finally all the little details - hip-high weeds on the left side of the tracks, and fewer weeds on the right side. The tracks are set right in the dirt - all those lessons about raising main tracks to make them look better maintained is a lot of bunk, at least for San Jose. The railroad’s telephone poles and signal poles frame the shot, reminding me of another detail to add. Then there’s the random debris - posts sticking up out of the weeds, the canvas in a pile on the side of the tracks, the scrap wire just past the WP tracks.

And if you look past that signal in the middle foreground, you’ll see a little shack on the right side of the tracks - that switchman’s shanty that showed up on the Dome of Foam engineering plans.And if I needed ideas about my buildings, there’s lots of great details that would apply, whether here or in another part of California: the corrugated iron fence around Standard Oil. The weathered low building for the empty prune sacks, with its big freight door and lots of windows high up. The packing shed with random gables and skylights poking out here and there.

Even the locomotive’s position gives me hints about how the tracks were used. None of the maps I had showed whether there was a track in that location, so I assumed there might be an interchange with the Western Pacific. Locomotive 1235 is sitting on a track in the right place; it might be an interchange track, or it might only be a spur for the Interurban railroad yards up on San Carlos Street. The photo also tells me I ought to be switching the industries along this track with a similar tiny 0-6-0.

Photos like these are waiting for you to find them. I couldn’t have imagined finding a photo like this when I started modeling the Vasona Branch, but I keep discovering photos like this. Each photo helps interpret the purpose of the different railroad tracks, identify the changes to the industries along the track over time, and hint at the set-dressing details that will make my models more realistic.

Your favorite railroad probably has photos like this - maybe you’ll see them in a book, or find some random photographer who snapped a photo of your favorite bit of track. (For example, if you model 1971-era Oakland, check out Nick deWolf’s photos of San Francisco and Oakland in the summer of 1971, which has some photos of local scrapyards and industries.)

The Barriger collection on Flickr is also huge, with a lot of very non-traditional photos of empty tracks, industries, and stations. Those photos also cover many railroads including the Western Pacific and Southern Pacific.

But I know there’s a bunch of photos out there that you’d love to find; just keep looking.

[Original photo from the Barriger collection at the University of Missouri; they're being quite generous to share the photos on Flickr, so go look at them and add comments explaining where these photos are. The Barriger collection is a set of photos taken by a railway exec in the 1930's and 1940's; check them out for some great discoveries.]