If we want to understand how a railroad and a cannery worked together, we need some data - preferably details about the number and types of freight cars doing to a particular industry. We’d done that in the past with Tom Campbell’s data about the grocery wholesaler’s siding in Sacramento a few years ago, but there’s always more we’d like to learn.

Getting information on the actual freight cars heading off to canneries is always a challenging task. Summary data often survives, either in terms of how many carloads the Santa Clara Valley sent, or canneries bragging about their canning prowess. Lawsuits might suggest the amount of traffic, such as this description of the fruit produced by several canneries. Although I’ve found occasional other facts (such as delivery notifications for freight cars at the Golden Gate cannery), the information’s spotty.

Luckily, occasional gems turn up. The Campbell Museum shared this Ainsley Packing Co. letterhead as part of reminding us of Campbell’s cannery heritage. They were most excited about the letterhead. I was most excited about the contents.

The letter gives the “pear account” of fruit coming to the Ainsley cannery from the Treat Ranch. It’s unclear where this ranch was. One possibility is a 160 acre ranch in Elk Grove run by the Gage family — which would explain why the fruit was arriving by rail on the Southern Pacific. There’s several other Treat Ranches that show up in searches; I’ll let someone else decide on the right one.

We see a carload of pears arriving every couple days from late July through early September. We see multiple carloads on August 3, but otherwise there’s usually a couple days between cars. There’s a larger gap at the end of the season, with 16 days between the arrival on August 24 and September 8.

What do we know about the freight cars? We can use the Official Railway Equipment Register (ORER) to track down what these cars were. The ORER was a frequently-published list describing each railroad's freight cars: reporting marks, size, weight, and special characteristics. Indexes in front can help us identify the owner from reporting marks. It was intended for use by shippers and others to check on the features of the cars they were assigned for loads.

We see 14 cars listed on the Ainsley receipt. (I’ve put them in a Google Docs spreadsheet if you’d like to examine the data in detail.) All are SP or subsidiary cars, suggesting the Treat Ranch was on the SP. Many of the cars come from the Texas subsidiaries, so they may not be familiar to us West Coast SP modelers. The GHSA is Galveston, Harrisburg, and San Antonio Railway, LW is Louisiana and Western, MLT is Morgan’s Louisiana and Texas.

They’re a mix of new and old cars; Most cars at least 15 years old, but two or three are new cars, built in the last few years. The twenty year old CS-2 ventilated fruit boxcars were common, showing up four times. Only one load is carried in a regular boxcar.

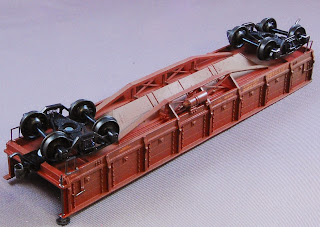

Half the freight cars are actually stock cars. I've certainly heard of stock cars being used for carrying fruit in high season. Melons were frequently carried in stock cars as late as the 1950's. However, this is a nice reminder how prevalent use of stock cars was for tree fruit. There’s also several mentions of “boxcar/stockcar” hybrids which I don’t know much about, and couldn’t find pictures.

The use of stockcars as a cheap ventilated boxcar is interesting, and could potentially be fun to model on the Vasona Branch. There's explicit evidence that stock cars carried fruit to canneries in the 1920's. Here's a photo showing workers unloading fruit from stock cars at the Richmond Chase cannery in San Jose. The Feb 1926 reweigh date for the nearest car indicates that apricots were still being carried in stock cars in the late 1920's. Note all the lug boxes are marked with the Richmond-Chase logo. If the cannery supplied the lug boxes, then that probably means the boxes needed to be shipped out to the farm by rail too. Doug Debs also pointed out a 1928 wreck of the Shoreline Limited passenger train at Bayshore involved the train slamming into several stock cars of apricots. The accident overturned the engine and forced some poor soul to go and recover the less-damaged apricots.

So, 14 carloads of pears, and 150 tons of fruit just from Treat. What does that tell us about the total amount of fruit arriving at the loading dock at the Ainsley cannery? How many more cars would have been arriving during the year? We can guess that from some of the news reports about the production at the Ainsley cannery. A 1918 news article, four years after these loads, mentioned that the cannery canned 5.5 million cans of fruit during the season. They spent $300,000 on fruit alone that year. Treat’s $7500 in pears would have been 2 to 2.5% of Ainsley’s total purchase, so if Ainsley bought the same amount of fruit in 1914 (and if all the fruit had the same price), we’d expect the equivalent of 750 cars of fruit coming in during the year, or six cars a day for 120 days. Now, not all of Ainsley’s fruit would have come by train; this is the Santa Clara Valley, after all, so pears, peaches, apricots, and plums would have been arriving by wagon. But I could also imagine that Ainsley would want to lengthen their canning season as long as possible, so bringing in fruit from elsewhere would allow them to can even when the orchards in Campbell weren’t producing. (On the other hand, we’re seeing fruit from Treat Ranch from mid-July to the beginning of September - a pretty wide season already.) It’s easy to assume that we’d have a few cars of fruit a day arriving at the Ainsley cannery throughout the season.

For my model railroad, this information gives me more details about the Ainsley Cannery, and how to make freight operations at the cannery better match what really happened in the 1930’s. First, this data suggests I should have cars coming to the cannery bringing fruit. If Ainsley was receiving fruit from elsewhere in the ‘teens, I can guess they were also receiving fruit from outside the valley in the 1930s. The use of stock cars for fruit is interesting and eye-catching, so I should should build a bunch of SP, EP&SW, and LW stock cars to bring in fruit. Finally, with so many cars coming in from Treat, I should definitely keep the Ainsley cannery busy - pushing many carloads at the industry, and also perhaps considering switching more than once a day to get realistic amounts of fruit into the cannery, and keeping my operators extra busy.

All of the research and guessing I’m doing here can be done for your favorite railroad or industry. Keep an eye out for paper and documentation, or check photos to see if you can spot the cars being loaded or unloaded at your favorite industries. Finding information on specific cars is easier than ever; Google Books has a bunch of ORERs on line. Westerfield also used to sell CDs with scans of particular years. I use Tony Thompson’s Southern Pacific Freight Cars books for more information and photos on the car classes.

Thanks to Ed Gibson for noticing the reweigh date on the stock car in the Richmond Chase photo, confirming that stock cars were used in the 1920's. Thanks to Doug Debs for pointing out the 1928 Bayshore wreck. Most of all, thanks to the Campbell Library for scanning and sharing the letterhead!